-

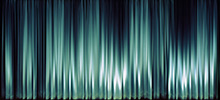

Cinestar Gütersloh, grün

122,5 x 263,3 x 7,5 cm -

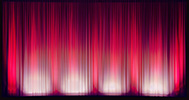

Cineplex Münster, rotgrün

122,5 x 226,9 x 7,5 cm -

Cinestar Hagen, grün

122,5 x 238,5 x 7,5 cm -

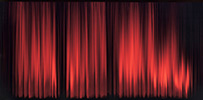

Cineplex Münster, rot

122,5 x 266 x 7,5 cm -

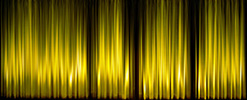

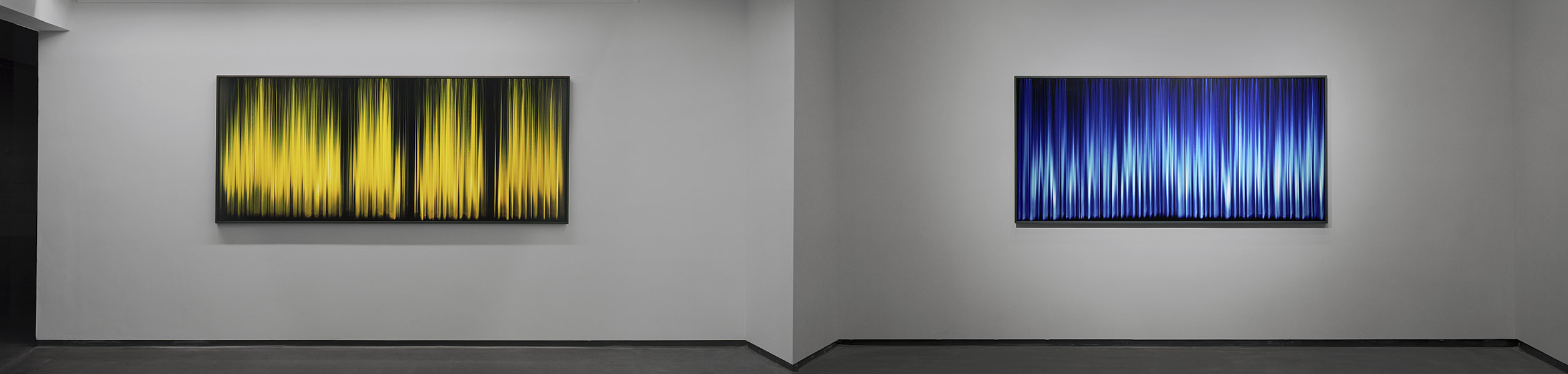

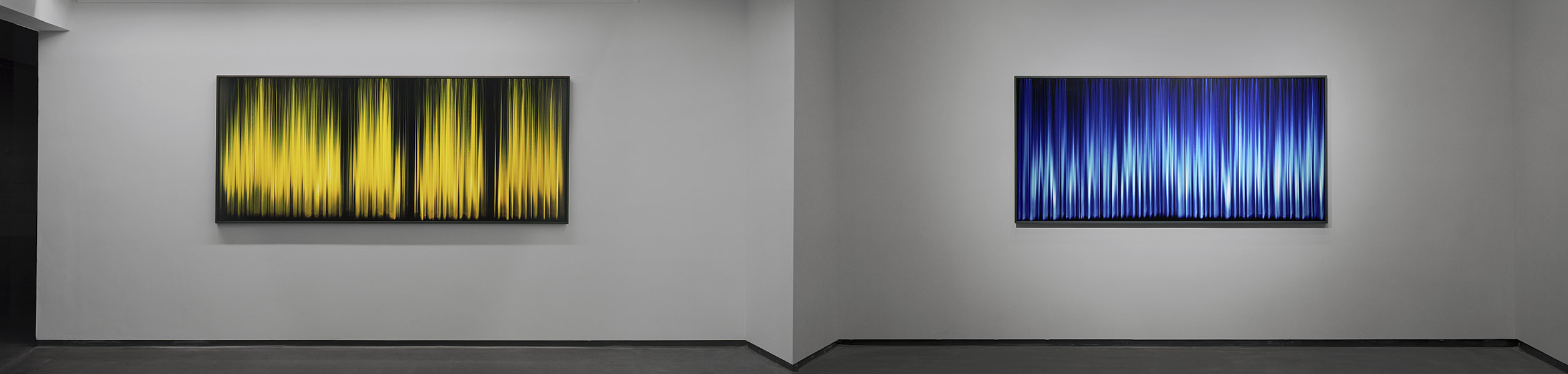

Cinestar Gütersloh, gelb

122,5 x 294,3 x 7,5 cm -

Cineplex Münster, Kontrast

122,5 x 244,3 x 7,5 cm -

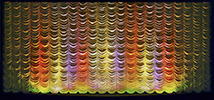

Cinemaxx Wuppertal, bunt

122,5 x 246,6 x 7,5 cm -

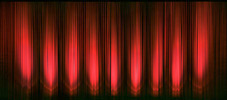

Cinestar Gütersloh, rot

122,5 x 244,1 x 7,5 cm -

Cineplex Münster, grau

122,5 x 232,6 x 7,5 cm -

Cinestar Hagen, Sterne

122,5 x 266 x 7,5 cm -

Cinestar Gütersloh, grau

122,5 x 241 x 7,5 cm -

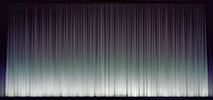

Cineplex Münster, weiss

122,5 x 246,6 x 7,5 cm -

Cinestar Bielefeld, blau

122,5 x 255,3 x 7,5 cm -

Cinstar Frankfurt, Perlen

122,5 x 245,5 x 7,5 cm -

Cinestar Bremen, rot

122,5 x 283,6 x 7,5 cm -

Cinemaxx Herten, weiss

122.5 x 258,3 x 7,5 cm -

Cineplex Paderborn, blau

122.5 x 283,5 x 7,5 cm -

Cinestar Frankfurt, grün

122.5 x 295,2 x 7,5 cm -

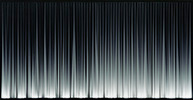

Cinestar Bremen, schwarz

122,5 x 281 x 7,5 cm

Lichtspiele

19 Farbphotos auf Aludibond, UV-schutzkaschiert, gerahmt, Edition 5, 2003-2005

19 color-prints, mounted on aludibond, laminated, framed, edition of 5, 2003-2005

»Neunzehn Vorhänge!«

Applaus für die »Lichtspiele« von Joachim Schulz

»Es werde Licht«: Wer kennt sie nicht, die erwartungsvolle Atmosphäre, die den Kinobesucher magisch umfängt, der aus der bergenden Dunkelheit in Richtung Leinwand blickt, wo das Kommende Ereignis werden und in Erscheinung treten soll. Zur Einstimmung, Stimulierung und Steigerung der Vorfreude werden zudem dem staunendem Auge kostbare Vorhänge geboten, die - ganz im Sinne einer wohldurchdachten Überwältigungsstrategie - dank rafnierter Faltenwürfe und dramatischer Ausleuchtung allemal mehr darzustellen haben als ein verheißungsvolles Präludium. Wenn sie sich nämlich feierlich-theatralisch öfnen, eröfnen sie nichts; es zeigt sich - und das ist das eigentlich Überraschende -, daß »nichts dahinter« ist, kein zu verbergender tiefer Bühnenraum, sondern nur eine etwa gleich große, fache, weiße Leinwand zur Projektion des Spielflms. Wie man sieht und kaum je bedenkt: Das ganze Zeremoniell des Öfnens (und am Ende der Vorstellung des Schließens) ist nur um seiner selbst willen da, ein Schauspiel für sich, ein bloßer Akt der Verführungskunst.

Joachim Schulz hat die Paradoxie, aber auch die Faszination dieses doch so altbekannten Phänomens ofenbar als erster erkannt, erkundet und in der neunzehnteiligen Serie »Lichtspiele« blendend-strahlend ins Werk gesetzt. Der Autor ist weit umhergereist, um die eindrucksvollsten, farbkräftigsten und spektakulärsten Exemplare aufzuspüren, und er ist außerordentlich fündig geworden. Die riesigen fotografschen Bilder der jeweils bildparallel aufgenommenen und formatfüllend abgezogenen Vorhänge versetzen den Betrachter unmittelbar in die Position und Lage des Kinobesuchers, in die gleiche verzaubernde, erregende Stimmung; zugleich aber verharrt er in einer Situation zur Refexion: Denn diese Vorhänge werden nie sich öfnen, sie kündigen nichts an; sie bieten sich der alleinigen, intensiven und im Vergleich untereinander sich steigernden Wahrnehmung dar. Die Licht-Bilder werden also nicht durch laufende Bilder, durch Licht-Spiele abgelöst, sie bleiben statisch. Vorhänge aus Schauspielhäusern sind in Joachim Schulz´ Repertoire nicht zu fnden; diese haben ja die nützliche Aufgabe, den tiefen Bühnenraum vor der verfrühten Einsichtnahme durchs Publikum zu schützen, wenn die Schauspieler und die Requisiten sich noch nicht an ihrem Ort befnden, das Spiel noch nicht begonnen hat; und wegen dieses funktionalen Eingebundenseins ins Theaterspiel wird dem genuinen Theatervorhang im Regelfall auch vergleichsweise wenig Beachtung geschenkt. Ganz anders liegt der Fall beim Kinovorhang: Zwar entstammt auch er der Tradition des Theaters, aber seine einzige Aufgabe bestand schon immer darin, das Lichtspielhaus durch Anspielung auf das Bühnenschauspiel zu nobilitieren, - galt das Kintopp doch zunächst eher als vulgäres Jahrmarkts- denn als Kunstereignis. Gebraucht wurde der Vorhang sonst eigentlich nie; das Kino kennt keinen Blick hinter etwaige Kulissen; die Leinwand liegt unmittelbar hinter dem Vorhang und bedarf keiner Verhüllung. War schon der Begrif »Film-Theater« euphemistisch intendiert, so war der Filmtheater-Vorhang stets ein Anspruch heischendes und Eindruck machendes Vehikel, ein interessantes, sich interessant machendes Beiwerk, ein dekoratives Kunststück. Faktischem Nutzen entbunden, konnte es sich verselbständigen und hybrid sich entfalten, sich bauschen und rafen nach gestalterischer Lust und Laune; aus einem der Schauspielpraxis dienenden Werkzeug wurden schließlich sich selbst auführende und feiernde Kunstwerke, die mittlerweile allerdings - so hat Joachim Schulz feststellen müssen - leider immer seltener werden. Und war der Faltenwurf in seiner Stofichkeit und Farbigkeit einst den Malern ein Vorwand, die Virtuosität des eigenen Metiers staunenerregend ins Bild zu setzen, gelingen derartige Inszenierungen heute durch opulente Materialien oder ingeniöse Lichtefekte, etwa eine expressionistische Beleuchtung von unten (die noch Albert Speers »Lichtdome« nachstellen). Nicht der illusionistische Traubenmaler Zeuxis, der Vögel zu täuschen vermochte, sondern der Vorhangmaler Parrhasios, der den Kollegen düpierte, war der wahre Meister in der Trompe-l´œil-Scheinwelt der Malerei, wie Plinius d. Ä. in seiner »Naturgeschichte« schildert; und dies gilt noch immer und besonders in der Scheinwelt des doppelten Scheins, die Joachim Schulz uns vor Augen führt.

Und was den Autor zudem an sein Thema bindet, ist, daß Fotografe hier ganz zu sich kommt und ganz bei sich bleibt. Die Analogien sind ofensichtlich, bedenkt man den dunklen Kinoraum, in dem der Film aufscheint, und die dunkle Kamera-Kammer, die foto-grafsch, also licht-schreibend, das Foto und den Film aufzeichnet; sie sind es aber auch mit Blick auf Kameraverschluß und Vorhang. Und so fach, so ohne räumliche Tiefe wie Kinovorhang und -leinwand einander aufiegen, so eng sind Thema und Technik in den Fotobildern von Joachim Schulz einander verhaftet. Oberfächliche Oberfäche im wörtlichen und Tiefe im übertragenen Sinne fallen in eins. Verschleiert wird nichts, denn Schleier und Vorhang sind es ja, die ins Licht gesetzt sind. Oder mit anderen Worten oder bei anderem Licht besehen: Unser Lichtbildner führt nicht hinters Licht, vielmehr bringt er ans Licht: Seine »Lichtspiele« sind in all ihrer Schönheit zwar purer Schein, aber ein Schein, der gerade nicht täuscht, sie sind vielmehr Ent-Täuschungs-Manöver. »Das wahre Geheimnis der Welt liegt im Sichtbaren, nicht im Unsichtbaren«, hat Oscar Wilde erkannt, und: »Alle Kunst ist zugleich Oberfäche und Symbol. Wer unter die Oberfäche dringt, tut es auf eigene Gefahr. Wer das Symbol liebt, tut es auf eigene Gefahr.« Höchst anschaulich, augenfällig und einleuchtend wird angesichts der fotografschen Bilder von Joachim Schulz: Die Oberfäche ist Symbol, in nuce. Darüber ließe sich noch vieles sagen. Einstweilen mag gelten das Brechtsche Fazit: »Der Vorhang zu, und alle Fragen ofen.«

Das große stille Bild

Das Saallicht geht aus. Spot auf den Vorhang. Der Zuschauer fast geblendet von der aus sich heraus scheinenden Stofflichkeit. Ein Abbild, das Objekt wird.

Schon in den Schaukästen vermischen sich die Grenzen von Bild und Objekt jenseits der Profanität von optischer Täuschung. "Tiefer hat man in Schaukästen bisher nicht geblickt" schreibt die hochdeutsche Zeitung, "[...]eine Leere, in der die Betrachtung Raum gewinnt."

Das Bild vom Vorhang lässt den Blick auf dem unmittelbar Gegebenen ruhen. Die Spannung, die der Zuschauer üblicherweise verspürt angesichts der Dinge, die sich wohl hinter dem Vorhang ereignen werden, wenn dieser sich öffnet, verlagert sich in die Fläche des Stoffes. Die Magie des Verborgenen gerinnt zu einem Punkt höchster Spannung. Vorhänge so verschieden wie die Filme und Theaterstücke, die sie inszenieren.

"Meine Vorhänge haben eine Spielfilmdauer von zwei Stunden", sagt Joachim Schulz als ein Vertreter des großen stillen Bildes.

Der photographische Virtuose und die Phantasmamorgie

Die Motivreihen von Joachim Schulz haben oft etwas von Verweigerung,

von Sperre, ob er nun verschlossene

Schweigende Oberflächen faszinieren ihn. Mit der Kamera bringt er sie zum Flüstern, Reden, zur optischen Kommunikation. Seine Photos entziehen das Motiv den geläufigen Erwartungen und fordern sie doch heraus. Sie geben dem Blick Raum und stimulieren die Vorstellungskraft.

Wir stehen fragend vor der erstaunlichen technischen Perfektion, photo-graphischer Brillianz, gestochener Schärfe und fasslicher Dreidimensionalität dieser Kinovorhänge. Ja, das IST photografiert, obgleich das Korn der Stofflichkeit des Tuches sich fast unlöslich mit dem Korn des Filmes deckt. Die Struktur erinnert an Malerei auf Leinwand, trotz großformatigem Hochglanzabzug. Ein verblüffender Einklang von Nähe und Distanz, von Verfremdung und Präsenz.

Wir begegnen der ausgebreiteten Frontalität des Vorhangs und dem Spiel der schimmernden, oft gleißenden Reflexe. Die Oberfläche erscheint zum Greifen, zum Anfassen detailgenau und haptisch. Nur der Vorhang, sein Faltenrhythmus und das Licht auf ihm existieren. Sie bestimmen das Bild. Jede zusätzliche Erhellung fehlt. Doch die lange, sehr lange Belichtungszeit macht das Leuchten wie aus dem Innersten möglich, selbst wenn alles reiner Oberflächenreflex bleibt.

Alle neunzehn Vorhänge haben ihr eigenes Lichtornament, je nach Stärke, Richtung, Streuweite des Scheinwerfers, je nachdem, wie hell oder dämmerig das Licht gedimmt ist. Je nach Dichte oder Weite der Faltungen und der Schwere des Stoffes. Unruhe und Wandel verbinden sich mit Übergängen in gleitender Gemächlichkeit. Einmal entsteht der Eindruck aufstrebender Bündelpfeiler: der einseitige Blick in ein Kirchenschiff. Dann wiederum ist das Licht oval konzentriert wie eine barocke Komposition, mit verschatteten Ecken und viel Weiß im Zentrum. Daneben schneidet das Licht spitz zulaufende Zacken aus der Nacht - Assoziationen an ein Kardiogramm. Ein anderes Mal modellieren die Falten den Stoff mit dem Regelmaß einer Säulenhalle oder erstarren in kleinteiliger Vertikalität. Ein unerschöpfliches Spektrum zwischen Fixierung und mählicher Veränderung, straffem Fall und gebauschter Fülle, einzig aus dem Zugriff des Lichts auf Farbe, Bewegung und Material.

Die Magie der Bilder lädt sich dabei mit Spannung, Erwartung und Vorstellung (im doppelten Sinne). Schulz beschreibt sein ideales Kino so: "Spot auf den Vorhang. Langsam öffnet sich der Vorhang, der Spot erlischt. Kein Film, nur kurze Dunkelheit. Langsam schließt sich der Vorhang, vom Spot erhellt. Das Saallicht geht an, Ende." Er fügt die Feststellung hinzu: "Meine Vorhänge haben eine Spielfilmdauer von zwei Stunden." Sie fassen diese imaginäre Vorstellung zusammen, verdichten sie zu einer Phantasmamorgie jenseits von Handlung und Erzählung, jenseits des Zelloloids, zum schieren "Lichtspiel", das sich selbst genügt und, wie nebenbei, klassische Themen der Malerei inszeniert: Vorhang, Draperie, Licht, Schatten, farbiger Verlauf, Abstraktion. Eine chromatische Verzauberung durch Licht, dem die Falten mit ihren Schattennestern antworten.

Langsam verstehen wir, warum dieses Programm bei Schulz zwei Stunden dauert. Kürzer, schneller geht es , bei Licht besehen, einfach nicht.

“Nineteen Curtains!”

Applause for Joachim Schulz’s “Lichtspiele”

“Let there be light”: Who has never experienced the expectant atmosphere which magically embraces the cinema-goer who, out of the sheltering darkness, gazes towards the screen, where the coming event will appear and come into being. In order to arouse, stimulate and heighten the anticipation, the admiring eye is presented with precious curtains which, owing to sophisticated drapery and dramatic illumination, make convincing use of an elaborate strategy of overpowering and thus manage to be undoubtedly more impressive than any promising prelude. For when those curtains open ceremonially-theatrically, they do not reveal anything; it shows – and this is the actual surprise – that there is “nothing behind”, no stage to conceal; there is just an almost equally large, flat, white screen for projecting the film. As one can see, but what is hardly ever considered: The entire ceremony of opening (and, at the end of the presentation, closing) only exists for its own sake, a spectacle in itself, a mere act of seductive art.

Joachim Schulz is apparently the first to have discovered, explored and translated the paradox, but also the fascination of this indeed well-known phenomenon into the dazzling and shining nineteen-part series “Lichtspiele”. The author travelled widely in order to seek out the most impressive, colourful and spectacular examples and succeeded exceptionally well. The huge photographic pictures of each curtain, taken parallel to the picture pane and printed full frame, put the observer into the place and position of the cinema-goer, in the same enchanting and exciting mood. At the same time, he remains in a state of reflexion: For those curtains will never open, they do not prefigure anything. They offer themselves to exclusive and intensive observation, which increases when the pictures are considered in comparison. Thus, those pictures of light are not replaced by moving pictures and light shows, they remain static. Theatre curtains cannot be found in Joachim Schulz’s repertoire, as they serve the useful purpose of protecting the stage from the audience’s premature gaze before the actors and props are positioned and the play begins. Because of this functional integration into the play itself, the genuine theatre curtain is usually paid comparatively little attention to, in contrast to the cinema curtain. Although the cinema curtain is derived from theatre tradition, its sole purpose has always been to ennoble the cinema by associating it with stage plays, as the cinema was initially regarded as a vulgar fair amusement rather than an art event. Otherwise, the curtain has never really been necessary: The cinema does not suffer from curious gazes behind potential scenery; the screen is positioned directly behind the curtain and does not need covering. Even the term “film theatre” was meant to be euphemistic; however, the film theatre curtain itself has always been an impressive device, begging to be acknowledged as culturally demanding, an interesting, attention-seeking embellishment, a decorative work of art. Discharged from its duties on stage, it gained independence and became a hybrid, artistically opening, billowing, and gathering at will. The former instrument of stage drama finally turned into a work of art, staging and celebrating its own performance. Unfortunately, the cinema curtain has indeed become quite rare by now, as Joachim Schulz had to realise. Once, the fall of the folds, because of its materiality and colourfulness, was the painters’ pretext to splendidly present their metier’s virtuosity; today, such impressions are created by using opulent materials and ingenious lightening effects, e.g., expressionistic lightening from below (which still imitate Albert Speer’s “Lichtdome”). As Plinius the Elder states in his “Natural History”, the real master of the Trompe-l’oeil illusory world was not the illusionistic grape painter Zeuxis, who was capable of deceiving birds, but the curtain painter Parrhasios, who duped his colleagues. This still holds true especially for the illusory world of double appearances that Joachim Schulz presents us with.

The author is further bound to his subject by the fact that in his series photography reconnects and remains with itself. The analogies are obvious when one thinks of the dark cinema auditorium where the film flashes up and the camera obscura which photo-graphically, i.e., by writing with light, records the photo and the film; or when one looks at camera shutters and cinema curtains. The cinema curtain lies on the screen as closely, without any spatial depth, as subject and technique are intertwined in Joachim Schulz’ photographic pictures. Superficial surface in the literal and depth in the figurative sense become one. Nothing is veiled, as veils and curtains are the very objects that are illuminated. In other words, or shown in a different light: Our artist of light and shade does not leave us in the dark, he brings something to light: His “Lichtspiele” are, despite their beauty, sheer appearances, but appearances that are exactly not deceptive; rather, they are manoeuvres of dis-illusionment. “The true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible,” Oscar Wilde realised, and: “All art is at once surface and symbol. Those who go beneath the surface do so at their peril. Those who read the symbol do so at their peril.” Joachim Schulz’s photographic pictures show very vividly, palpably and perspicuously: The surface is symbol, in nuce. A lot more could be said about this. For the time being, Brecht’s conclusion is valid: “The curtain closed and all questions open.”

The large, silent image

The overhead light goes out. Spotlight on the curtain. The onlooker is almost dazzled by the physical presence of the textile, which shines from within. An image that becomes an object.

In the display cases, the artist blurs the borders between image and object in a manner that goes beyond the profanity of optical illusion. "Nobody has looked this deep into display cases before," writes the High German press, "[...] an emptiness in which observation gains space."

The image of the curtain has our gaze rest on what is immediately given. That tension the beholder normally feels in relation to those things that will presumably happen behind the curtain once it opens is now triggered by the material's surface. The magic of what is concealed congeals into a point of climatic tension. Curtains that are as different as the films and plays that they stage.

Joachim Schulz, an exponent of the large, silent image explains: "My curtains have a playing time of two hours".

The photographic virtuoso and the phantasmagoria

Irrespective of whether he photographs sealed bunkers , empty display cases with no notices in them, or closed cinema curtains , Joachim Schulz' series on specific topics are often redolent with refusal or barricades.

Silent surfaces fascinate him. Using his camera he induces them to whisper, talk, to engage in visual communication. Though his photographs strip his topic of the customary expectations, the images provoke such all the same. They widen the gaze's scope and stimulate our imagination.

We stand questioningly in front of this startling technical perfection, photographic brilliance, ultra-sharp quality and the tangible three-dimensional aspect of these cinema curtains. Yes, these ARE photographs, even though the grain of the curtain's material is almost identical to that of the film. Though these are large-format glossy prints, the structure is reminiscent of painting on canvas. The result is a bewildering unison of closeness and distance, of alienation and presence.

We encounter the extended frontal view of the curtain and the interplay of the shimmering, often glaring reflexes. With its tactile qualities and exact detail the surface invites you to touch it. All that exists are the curtain, the rhythm of its folds, and the light on it. These elements define the image. No additional lighting is used, but the long, in fact extremely long exposure time produces a glow that seems to come from deep within even though only surface reflections are at work.

In each of the 19 curtains the light effects vary according to the intensity, direction, and diffusion of the spotlight, and depending on how brightly or muted the light is dimmed. And they are influenced by the thickness and width of the folds, not to mention the heaviness of the material. Restlessness and change combine with transitions into smooth composure. Sometimes there is an impression of soaring clustered columns: a sideward glance into a church nave. Other times the light is an oval concentrated like a baroque composition, with corners in shadow and abundant white at the center. In the next curtain the light cuts sharp points out of the night - recalling a cardiogram. Another time the folds mold the material with the regularity of a colonnade or freeze into small vertical portions. An inexhaustible spectrum between fixing and gradual change, rigid creases and burgeoning expanse, produced solely by the effect of light on color, motion and material.

In the process, the magic of the images is suffused with tension, expectation, imagination and performance. Schulz describes his ideal cinema experience as follows: "Spotlight on the curtain. It opens slowly and the spotlight goes out. No movie, just darkness for a brief time. Slowly the curtain closes and the spotlight brightens again. The overhead light goes on, The End." He further explains: "My curtains have a playing time of two hours." They summarize this imaginary performance, focus it into a phantasmagoria beyond action and narration, beyond the celluloid, until it becomes a sheer "play of light" that requires nothing more and, seemingly in passing orchestrates classic topics of painting: Curtain, drapery, light, shadow, color development, abstraction. A chromatic enchantment produced by light, which the folds respond to with their clusters of shadow.

Gradually, we understand why Schulz' program lasts two hours. It is simply not possible when you examine it in clear light to make it shorter or quicker.